Before the outbreak of World War II on September 1, 1939, Jan Karski was a Polish reserve officer and a junior diplomat with large ambitions and a bright future. On September 17, 1939, Soviet forces invaded his country from the east, and Karski’s life was sent careening in a new direction. Rounded up along with thousands of Polish officers, policemen, and leading citizens from the eastern part of his country, he would have been sent to his certain death at Katyn Forest, but managed his first escape. Posing as an enlisted man, he fled Soviet captivity and returned to the German Nazi-occupied part of Poland.

Before long, Karski became a courier for the Polish Underground resistance, where he played a large and remarkable role in the struggle for his country, putting his life on the line numerous times. After being tortured by the German Nazis, he attempted suicide, but later continued his mission of smuggling information out of Poland to the Polish Government in Exile, first in France and later in England. On his return trips to Poland, he would return with orders and information for the Underground authorities. Drawing on his photographic memory, he delivered the Polish Government in Exile’s orders for merging a full-fledged Underground state into the country’s already strong military resistance.

On one of his many courageous missions, an unshaven Karski twice infiltrated Warsaw’s Jewish Ghetto to witness its horrors, including – what Karski later described – “degradation, starvation and death.” An especially gruesome spectacle was watching young Nazi soldiers hunt down Jewish children for sport. Karski subsequently posed as a Ukrainian guard at the Izbica transit camp to witness Jews being herded onto train cars, to be sent to their deaths.

After his final mission from Poland, Karski was ordered to spread the word in the West about what he’d seen. In addition to detailed written reports, he personally delivered his eyewitness account – and urgent appeal for intervention – to British Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden and later President Franklin Roosevelt in the White House. He pleaded with both leaders to stop the Holocaust. Sadly, his message largely fell on deaf ears.

In addition to meeting with Roosevelt on July 5, 1943, he met with Supreme Court Justice Felix Frankfurter, a close friend of the president. Karski remembers Frankfurter’s reaction: “‘Mr. Karski,’ he says emphatically, ‘A man like me talking to a man like you must be totally frank. So I must say: I am unable to believe in what I have just heard, in all the things that you have just told me.’ ”

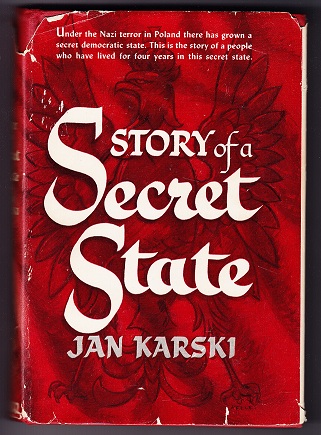

Once in America, Karski was assigned by the Polish Government in Exile to write his account. Improbably, his book, Story of a Secret State, was published in 1944 in the United States and became an overnight best-seller, being picked as a Book of the Month Club selection and selling 400,000 copies. This opened the door for Karski to conduct an extensive speaking tour throughout the United States and Canada, influencing public opinion.

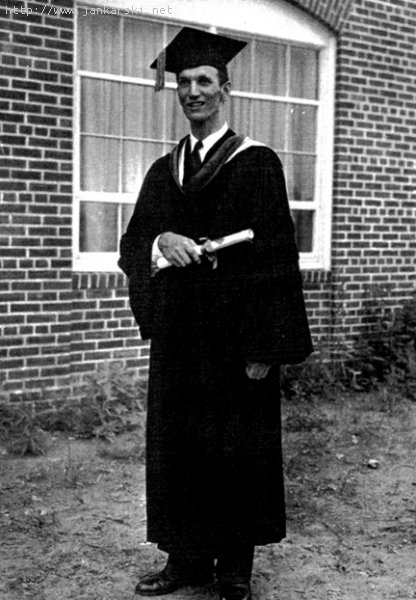

After the war, choosing to remain in the United States rather than return to Communist Poland, he earned his Ph.D. at Georgetown University, where subsequently he taught in the School of Foreign Service for 40 years. Among his notable students were: Daniel Fried, former Assistant Secretary of State for European and Eurasian Affairs and former U.S. Ambassador to Poland, Stephen D. Mull, a Senior Foreign Service Officer and former U.S. Ambassador to Poland and to Lithuania, Deputy U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations Kenneth Adelman, Governor of Illinois Patrick Joseph Quinn Jr., and U.S. Senator Richard Joseph Durbin of Illinois*.

Initially loath to speak about his wartime experiences, wanting to put that horrific chapter behind him, ultimately, he had no choice but to speak out. “I have no other proofs, no photographs,” Karski wrote later in a memoir about witnessing Jews being sent to their deaths. “All I can say is that I saw it, and that it is the truth.” Half a century later, Karski told Maciej Kozlowski, author of the biography, The Emissary: The Story of Jan Karski. “I spent about an hour in that camp. I came out sick, seized by fits of nausea. I vomited blood. I had seen horrifying things there. Disbelief? You would not believe it yourself, if you saw it.”

In addition to Story of a Secret State, Karski also published The Great Powers and Poland, 1919-1945: From Versailles to Yalta, an insightful analysis of the politics of power. In 1982, Yad Vashem in Jerusalem awarded him the title of a Righteous Among the Nations, and the Israeli government declared him an Honorary Citizen in 1994, as did his native city of Łódź. He was also awarded two high honors from Poland, the Order of the White Eagle and the Virtuti Militari. Karski’s extraordinary legacy was recognized by President Barack Obama on May 29, 2012, when he was decorated posthumously with the Presidential Medal of Freedom, America’s highest civilian honor.

According to biographer Kozlowski, “There could hardly be another person who felt more deeply, painfully, and bitterly the expedient abandonment of Poland by the Allies in World War II. Jan Karski was a man who, tragically, had to feel that his own prodigious efforts on behalf of the Jews of Europe - and on behalf of his briefly independent native land - were an utter failure. Regarded as a hero in both Poland and Israel, his was a heroism not of triumphs but of extraordinary integrity and courage.”

Born Jan Kozielewski in 1914 in Łódź, Poland, Karski was the youngest of eight children in a Roman Catholic family. His father was a leather merchant. His hometown was a heterogeneous city composed of Polish Catholics, Polish Jews, Germans, and Russians. Young Karski studied law and diplomacy at the University of Lwow (Lviv). Though Jan Karski's large ambitions and bright future failed to place him on the course that he had imagined as a youth, he ended up playing an enormous role on the world stage, offering lessons to us all. His mission was courageous, his testimony powerful, the moral standards he set for himself and others of the highest order; indisputably, he became Humanity’s Hero.

In 1965, he married Pola Nirenska, a Polish Jewish dancer whom he had first seen perform in London in 1938. In yet another tragedy in Karski’s life, his wife took her own life in 1992.

*Some sources wrongly claim President Bill Clinton was also Karski’s student. In an email sent to the Foundation on June 22, 2022, Amanda Ruthven of the University Registrar for Academic & Student Records at Georgetown University stated, "After extensive research through the university's archives, we have concluded that President Clinton did not take classes with Jan Karski." However, President Clinton was a Georgetown student during the time that Karski was teaching. He stated this in his letter of support for the Presidential Medal of Freedom, in which he wrote, “In my time at Georgetown, I was fortunate to study in the School of Foreign Service during Dr. Karski's remarkable tenure. His expertise in international relations was without comparison, and he was widely known as a force of clarity and wisdom.” But note that President Clinton's own tribute letter about Karski of July 17, 2000, does not mention being his student.